Historian Dennis Evanosky at the Cohen gravesite [Photo by Michael Colbruno]

[Biography by Dennis Evanosky; reprinted from the August 11, 2008 Alameda Sun]

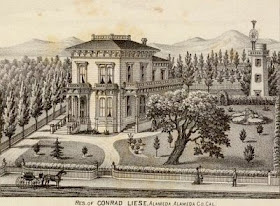

Look at a map of San Francisco's Tenderloin district between Leavenworth and Hyde streets and you'll find Cohen Place, named for Alfred Andrew Cohen. This gated alleyway's moniker might raise a question for most Alamedans. How did the man who built Fernside in their city have a street, humble as it is, named for him in San Francisco? The answer reveals what most Alamedans do not know about Cohen: he (and his money) wielded considerable influence in Gold Rush San Francisco.

In the 1850s Cohen was a respected and trusted financier and banker. He rubbed elbows with — and on at least one occasion clashed with — another San Francisco banker, William Tecumseh Sherman. The respect and trust that some felt for Cohen vanished in 1855, however, when rumors spread that he played a major role in what his contemporaries called "Black Friday."

Alfred A. Cohen was born in London, England, on July 17, 1829, the son of a wealthy merchant. Stunning news reached the family just a month after Alfred's fourth birthday. On Aug. 28, 1833, King William IV had freed all the slaves in his kingdom. "Whereas divers Persons are holden in Slavery within divers of His Majesty's Colonies, it is just and expedient that all such Persons should be manumitted and set free," the decree read.

Among the family businesses that included wine and money-brokering, the Cohens owned a coffee plantation in Jamaica. Since this enterprise depended on slave labor to squeeze the profits from its popular bean, the Cohens found themselves in financial straits. They could no longer afford to live in London and moved to Exeter in Devonshire where Alfred attended school until 1841. By age 14, he had returned to London to work for a solicitor. Two years later he immigrated alone to Canada where he earned his living in a variety of jobs.

In 1847, Alfred left Canada for the West Indies. He joined his older brother Frederick's mercantile business in one of the family's old footholds in the New World, Jamaica. In 1849, the thought of striking it rich in far-off California got the better of Alfred and he headed west. At first he settled in Sacramento, where he established the commission firm of Alfred A. Cohen.

By 1852 he had moved to San Francisco where his brother joined him. Alfred had prospered enough to mingle with San Francisco's high society. He cemented his membership in that elite circle when he married. Emilie Gibbons, daughter of prominent San Francisco physician Henry Gibbons, in 1854.

Barely a year into his marriage on Thursday, Feb. 22, 1855, news arrived that the major St. Louis bank Page, Bacon & Co. had serious financial problems. This news precipitated a run on San Francisco banks. The Page, Bacon branch closed immediately.

The next day, depositors lined up at the doors of other San Francisco banks: Price, Rodman; Miners' Exchange; Robinson & Co.; Wells, Fargo and Adams & Co. They demanded their deposits in gold. Many found themselves penniless in the streets, however, and remembered the day as "Black Friday."

Before Adams & Co. opened its doors that morning, the board of directors declared bankruptcy; the courts appointed Alfred Cohen receiver. So while its depositors waited outside for Adams & Co.'s customary opening time of 10 a.m., the bank's money was already "legally" in Cohen's hands.

Cohen discovered that Adams & Co. had not only cooked its books but had made a "quiet run" on the bank and withdrawn $250,000 before the doors opened on Black Friday. Unfortunately for the hoi-polloi waiting outside in the February chill, little was left for them.

Although Cohen was nothing more than the bearer of very bad news, he was made the scapegoat. A warrant for his arrest was issued. In an attempt to escape, Cohen concealed himself in the hold of the steamer Uncle Sam bound for Nicaragua, to no avail. On Jan. 5, 1856, deputy sheriff John Harrison came aboard warrant-in-hand and arrested Cohen.

Cohen did little to help his cause. In his memoirs William Tecumseh Sherman — who was working as a banker in San Francisco at the time — accused Cohen of spreading false rumors about his bank, Lucas, Turner & Co.

Cohen's older brother Frederick also involved himself in the shenanigans. On Feb. 12, 1857, he assaulted San Francisco Bulletin editor (and Adams & Co. manager) James King of William.

"A cowardly attack was made Wednesday, about 10 o'clock, by F.A Cohen, brother of A.A. Cohen, on Mr. Thos. S. King, the editor of the Evening Bulletin," the Alta California reported. "(This) resulted in the latter being beaten over the head by Cohen and the wounding of Cohen in the neck by a pistol ball fired by Mr. King."

The article went on to describe the confusion that ensued after the assault. The reporter likely did not notice that he had stoked the fire himself by confusing Unitarian minister Thomas Starr King with the Bulletin's editor, James, King of William.

By then Alfred had likely had enough of San Francisco. While in jail, he studied the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1857. He was looking forward to getting out of town. He would still keep his fingers in politics. He had already wrangled himself an appointment as justice of the peace in Alameda County.

He settled in on some property across the Bay that he had obtained from a pair of his clients, W.W. Chipman and Gideon Aughinbaugh.

Click here to purchase Dennis Evanosky's book about Alameda.

_________________________________________________________________________

[Photo of Edgar Cohen gravemarker by Michael Colbruno]

Edgar A. Cohen was a famous photographer and the son of Alfred A. Cohen. Some of his earliest pictures are of Fernside, the Cohen family estate in Alameda. Cohen traveled all over the state, and photographed Yosemite and most of the Missions. He was in San Francisco for the earthquake and documented the ruin of the city. He called Monterey County, "the best place to photograph over any place I know." Cohen used a 5" x 7" Premo No. 6 (a folding field camera).

Cohen died from complications resulting from being hit by a 12-year-old boy on his bicycle.

Subscribe to Michael Colbruno's Mountain View Cemetery Bio Tour by Email